10. Experience More Access

Jennifer Mei

Introduction

Did you know, according to Statistics Canada (2017), 22% of Canadians live with at least one disability? That is 6.2 million people! Of these Canadians, 13% are youth, ages 15 to 24, and 20% are working age adults, aged 25 to 64. Disability impacts employees and students. The employment rate for people experiencing disability is only 50%. The employment rate is 80% for those who do not experience a disability (see Figure 10.1).

Did You Know?

Learning Objectives

After carefully reading this chapter, and completing the exercises within it, you should be able to:

- Indicate how you would apply your self-identity in a systemic construct of disability.

- Identify your social location.

- Identify a strengths-based approach.

- Complete a self-evaluation of your functional impacts and related accommodations.

- Identify your human rights.

- Identify microaggressions.

- Find support service resources in your community.

Disability or not?

The Identity Crisis of Disability

This chapter discusses the importance of understanding the term “disability” and how it is used during the job search process and in the workplace. Even if you do not identify with having a disability, reading this chapter will allow you to gain a deeper understanding of how to be a more inclusive colleague to those who do.

If you are a student who requires a customized workplace environment or accommodations, this chapter is intended to support you in navigating an often-challenging system.

The academic theory behind this chapter is anti-oppressive, which honors differences and questions societal norms (Brown & Strega, 2005, p. 39). This chapter also reflects a strengths-based perspective, which aims to reframe the negative language we often use into positive language.

Society is not very flexible when it comes to defining disability. The Centers for Disease Control and Protection (CDC) (2020) offers the following:

A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions). (para. 1).

Unfortunately, “a one society fits all model does not take differences into account, therefore creating inequity” (Barile, 2002, p. 2).

In this chapter, we rely on the above definition critically — with an understanding that not everyone identifies with this definition.

Figure 10.2 illustrates a one-size-fits-all definition of disability, from the Centers for Disease Control and Protection (2020), where impairment is defined as a “problem with body function or structure”; activity limitations means “there is difficulty executing a task or action;” and participation restrictions are “problems with involvement in life situations.”

Disability as Defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Protection

“Disability,” as defined above or a variation thereof, is a term that some individuals who live with a disability choose to use to define a health condition that impacts their functioning. Areas of functioning that may be affected by disability are:

- Physical health

- Mental health

- Neurological

- Developmental

- Sensory

For the purposes of this chapter, the term “disability” will be used to encompass an ongoing medical condition that impacts a person’s functioning, and to acknowledge, from a human rights perspective, the legal context in which the term “disability” is commonly used.

A Difference in Perspective — Medical Model versus Social Model

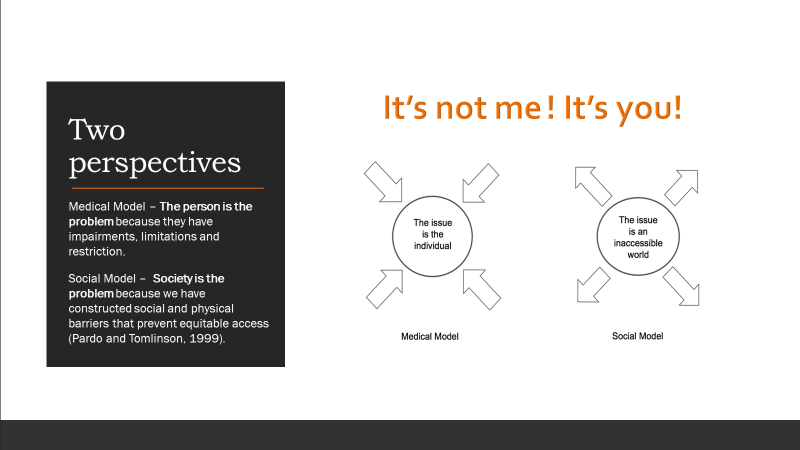

The WHO definition of disability arguably reflects a medical model commonly used when determining one’s eligibility for accommodations in the workplace. In this model, the person is seen as the problem because they have impairments that impact their ability to participate fully in their environment.

The social model, on the other hand, suggests that removing social, political, and environmental barriers is a step towards open access, and reframes the concept of disability as socially constructed (Larson & Robertson, 2018, p. 56–57). In the social model, the problem is an inaccessible world. (See Figure 10.3 for an illustration of the medical and social model perspectives.)

Two Perspectives on Accessibility: The Medical Model and the Social Model

In a narrative statement, Piepzna-Samarasinha (2018) describes the environmental barriers that often impact people with disabilities.

We know that for many of us, access is on our minds when it comes to traveling, navigating the city, movement spaces, buildings, sidewalks, public transportation, the air, the bathrooms, the places to stay, the pace, the language, the cost, the crowds, the doors, the people who will be there, and so, so much more (p. 47).

Analogy to Illustrate Systemic Barriers

Imagine a group of friends got together and built a maze. The maze was complicated, but most of the friends in the group were successful in finding their way around. Eventually, everyone got so comfortable navigating the maze that they forgot it was a maze at all. (See Figure 10.4.)

Maze Analogy – Systemic Barriers

What the group did not realize was that others who were not part of building the maze, were new to the maze, or were different from the group that built the maze, were rarely successful at finding their way around. They were very aware of the maze around them and found it uncomfortable, difficult, or impossible to navigate (Figure 10.5). The meaning or moral illustrated in this analogy is that some people created a system or maze in which they were comfortable navigating, but they created barriers for others whose access is therefore denied within that system (Figure 10.6).

Maze Analogy – The Outcomes of Systemic Barriers

Maze Analogy – The System Created Barriers

In the next section, we will explore how you may define yourself within a systemic (medical) model of disability, and discuss ways this information can help you navigate possible job search and employment barriers.

How Does This Apply to Me?

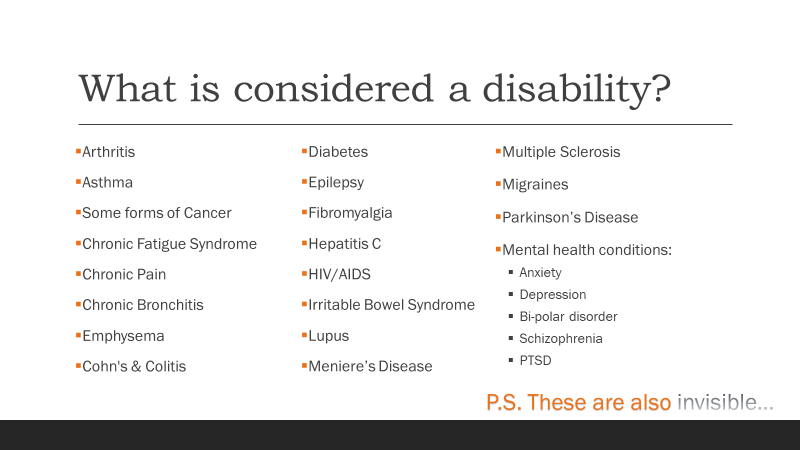

Conditions that May be Systemically Defined as a Disability

As described in A Difference in Perspective, some people with ongoing functional impacts may self-identify as a person with a disability, and some do not (Larson & Robertson, 2016, p. 46). The concept of being the expert on one’s own experience and identity is often referred to as self-determination (Stroman, 2003, p. 209).

It is important to note that the umbrella definition of “disability” (WHO Africa, n.d.) is used by many service providers and agencies to systemically validate accommodations and other disability-related services (Larson & Robertson, 2016, p. 59).

Figure 10.7 provides a few examples of health conditions that are considered disabilities by the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction (2022), under the WHO definition.

Conditions that are Considered a Disability

How Do I Identify?

People who do not self-identify as a person with a disability may define the impacts of their functioning differently. They may use one of the following terms or something similar:

- Medical condition

- Health condition

- Long-term injury

- Short-term injury

- Diverse-ability

- Different abilities

- Mental health condition

- Mental illness

- Disability — but with a different definition

- No disability — disability is a social construct

Exercise 10.1 Applying Self-Identity in the Societal Construct of Disability or “Maze”

Reflect on the following questions:

- How do you define yourself as a person with ongoing functional impacts (i.e., disability or health condition)?

- How will knowing your self-identification help you navigate requesting accommodations and services in a systemic construct of disability?

Exercises 10.1 to 10.6: Activity Worksheet 1-6 [PDF]

Social Location

How Do I Find Where I Fit into Society?

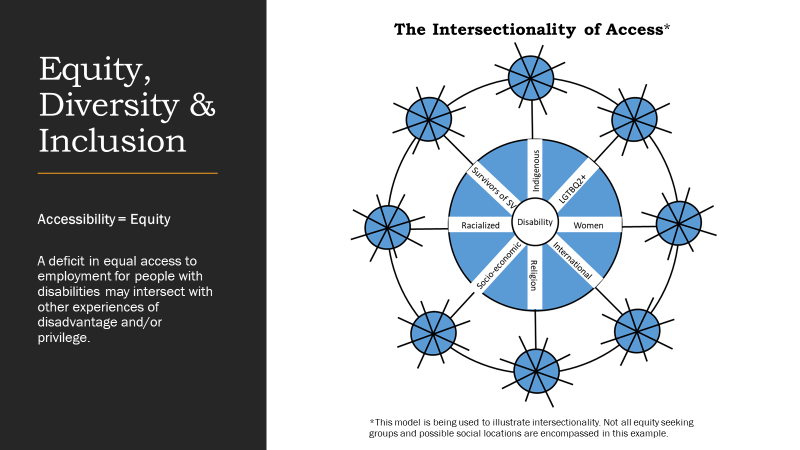

This section discusses how knowing your social location can help you navigate the societal barriers to employment that affect people with disabilities. According to Statistics Canada (n.d), there is currently a deficit in equitable access to employment for people with disabilities. Understanding where you are socially located may help you advocate for yourself in hopes of working towards a more equitable, diverse, and inclusive society.

It’s also important to note that sometimes living with a disability can coincide with other lived experiences of physical, mental, and social privilege or disadvantage. Disadvantages exist because society often makes assumptions about what people who have differences are capable of doing, including within the workplace.

Intersectionality is a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity of the world, in people, and in human experiences (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Figure 10.8 illustrates how different lived experiences may intersect. You may find that using the concept of intersectionality as a tool to find your social location is helpful in understanding your social interactions. Knowledge of intersectionality can also constructively inform how you communicate with others during the job search process.

This information can help determine when your experiences have helped you cultivate your strengths as well. For example, you may notice that during times of challenge, you were extremely resilient. Remember to let your strengths shine through. See section Taking a Strengths-Based Approach to Job Searching for more information about using a strengths-based perspective.

A deficit in equal access to employment may intersect with other experiences of disadvantage or privilege.

The Intersectionality of Access

Exercise 10.2 Finding Your Social Location

Take the Privilege-Test (PDF) and then, after you’ve completed the quiz, answer the additional questions below. This quiz will help you better understand your social location by illustrating your areas of advantage and disadvantage in society.

- How will what you have learned about your social location help you navigate the job search process?

- If you are not a person with a disability, how will you work towards becoming a good ally?

- If you have access, put your results further into context by watching the following video on Facebook Watch, What Is Privilege? #AustraliaDay, (https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1936578223240531) from BuzzFeed Australia (2017).

Note. Test questions in the PDF were sourced from What is Privilege (Harvey et al., 2017) on the BuzzFeed website.

Exercises 10.1 to 10.6: Activity Worksheet 1-6 [PDF]

Allyship

The concept of allyship is multi-layered and requires unpacking complex relationships between people’s power, privilege, and disadvantage. Therefore, acknowledgment is made that this section barely scratches the surface of this topic. However, it will be discussed here briefly to signify the importance of allyship in the workplace.

Allies support the empowerment of people with marginalized identities by genuinely listening, learning, and interacting without judgment. It’s important to note that the person who discerns whether someone is an ally is the person who is marginalized.

If you are a person without a disability, listen to people with disabilities as experts of their own experiences, and be prepared to learn from them. Then, look critically at how your own social location informs the way you think and feel about disability. Can you identify any assumptions and biases you may hold about people with disabilities?

Allyship requires vulnerability and knowing when to surrender your power so that you can hold space for marginalized voices. In the workplace, that might mean giving someone a chance to speak from their perspective, or standing up against a discriminatory comment during a meeting. Working towards becoming a supportive colleague and ally helps create a more inclusive workplace.

Now that you have learned about self-determination, social location, and allyship, let’s move on to navigating the job search process.

I’m Ready to Job Search. Now what?

Taking a Strengths-Based Approach to Job Searching

Using a strengths-based approach to requesting accommodations shows the employer that you are capable and qualified for the job. Remember, disclosing your disability is not necessary in an informational interview, employment interview, cover letter, or resume. However, it is important to notice how you speak about yourself. Sometimes we inadvertently use negative or deficit-based language to describe our skills and abilities (University of Michigan, 2019).

Example:

- I can’t sit for long periods of time because I have a bad back.

- I can’t do that task, because the stress will trigger my mental health.

- I can’t follow written instructions, because reading is a barrier for me.

Instead, try reframing your language to reflect your strengths.

Example:

- I can sit for long periods of time in an office chair with a back.

- I can do that task with short breaks to stay focused.

- I can quickly absorb information when I use a text–to–speech app.

Unless having a healthy back, excellent mental health every day, and reading perfectly are bona fide requirements of the job description, your functional impacts are likely unrelated to whether you are qualified to do the job. There may be an accommodation that will help mitigate your impacts and allow you to meet the job requirements.

When presenting yourself during the job search process, remember your unique abilities may positively set you apart from other candidates. Using a strengths-based perspective, focus on why you believe you are capable and qualified for the job. The activity in Exercise 10.3 provides examples of how to use strengths-based language in your job search approach, and how to request accommodations if needed.

Exercise 10.3 From Deficit-based Language to Strengths-based Language

Change the following deficit-based statements to strengths-based statements.

Example:

Deficit-based language – I have a learning disability in written output so I can’t take notes.

Strengths-based language – I take excellent notes with the text–to–speech app on my phone.

- I don’t understand verbal instructions.

- I can’t stand for long periods of time.

- I have trouble with time management.

- I don’t understand social cues or interactions.

- I can’t focus or concentrate on my work sometimes.

Try changing some of your own deficit-based language into strengths-based language.

Exercises 10.1 to 10.6: Activity Worksheet 1-6 [PDF]

Got the Job! How Do I Get Accommodations?

Requesting Workplace Accommodations

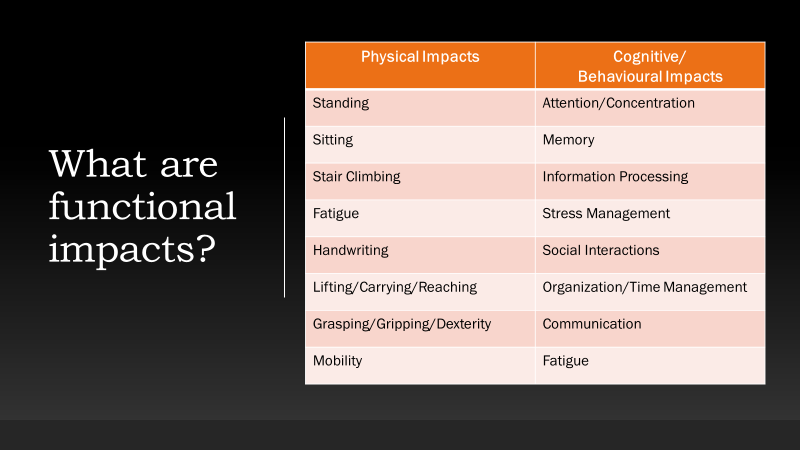

As a person with a disability, you have a right to workplace accommodations (see section Identifying Your Human Rights). If you need to ask your employer for accommodation, self-assess how your diverse ability impacts your functioning in the workplace (see Figure 10.9 Functional Impacts and Figure 10.10 Examples of Accommodation). This process of requesting accommodations will likely lead you through several systemically-informed steps.

When requesting accommodations, remember to highlight your strengths and how you believe the accommodation will help you meet the expectations of the job.

Examples of Functional Impacts

Examples of Accommodations

Disclosing Your Disability

You may feel that disclosing the nature of your disability will help your employer understand how to best work with you (see Figure 10.11 for ways to describe the nature of your disability). If so, remember your formal diagnosis (i.e., Generalized Anxiety Disorder, migraines, etc.) is confidential. How much information you would like to share with your employer is your choice. Any disability-related information would best be disclosed to the designated human resources officer who can assist you with the process of requesting accommodations.

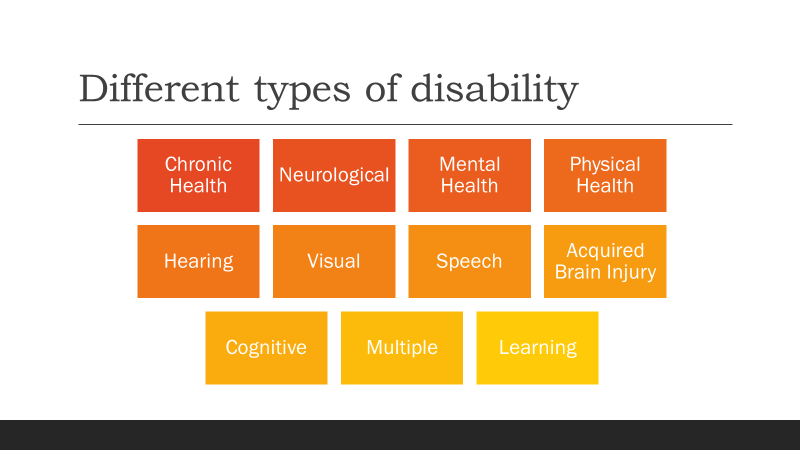

Different Types of Disability

Getting Asked for Medical Documentation

Your employer may ask you for medical documentation to support an accommodation. Make sure to clarify which healthcare professionals are considered qualified to provide this information. Examples of certified healthcare professionals include:

- Family physician

- Specialist

- Psychiatrist

- Audiologist

- Optometrist

- Surgeon

Keep in mind that some medical professionals charge a fee to fill out forms. Documentation from healthcare professionals, such as a naturopathic doctor, counselor, nurse, social worker, or physiotherapist, may not be considered valid medical documentation because these clinicians are unable to confirm the presence of a clinical diagnosis.

Visiting Your Medical Professional

When asking your healthcare professional to provide documentation, ask that they include:

- Information about how your disability impacts your functioning;

- Recommendations for your accommodation(s); and

- Confirmation of a diagnosed disability/health condition.

Exercise 10.4 Functional Impacts and Possible Accommodations

Complete a self-assessment of your functional impacts and possible accommodations.

-

- From the lists below, identify your functional impacts. Add any functional impacts that are not listed here for you.

Examples of Functional Impacts

-

-

- Physical

- Standing

- Sitting

- Stair climbing

- Ambulation (cane, wheelchair, etc.)

- Fatigue

- Handwriting

- Lifting/ Carrying/ Reaching

- Grasping/ Gripping/ Dexterity

- Keyboarding

- Other: ________________

- Cognitive or Behavioural

- Attention and concentration

- Memory

- Information processing (written/ verbal)

- Stress management

- Social interaction

- Organization

- Time management

- Communication

- Fatigue

- Other: ________________

- Physical

- What are some possible accommodations that help mitigate your functional impacts in a career/ experiential learning environment? Note: Some accommodations may be helpful for many types of functional impacts (i.e., physical and cognitive/ behavioural).

-

Examples of Possible Accommodations

-

-

- Flexible schedule

- Extra time to learn and do tasks

- Comfortable office chair

- Speech-to-text software

- Text-to-speech software

- Accessible office space

- Reduced lighting

- Regular breaks

- Organization/Time management software

- Sign language interpreter

- Communication

- Sit to stand desk

- Distracted-reduced environment

- Care assistant

- Closed captioning

- Ergonomic station

- Background music

- FM system

- Other: ______________

-

Exercises 10.1 to 10.6: Activity Worksheet 1-6 [PDF]

If you are a student in a career/experiential learning placement, contact your co-op coordinator or career advisor if you require further assistance to determine your workplace accommodations. If you are a student in a practicum or clinical placement, contact your practicum supervisor or accessibility services advisor for assistance.

What Are My Rights?

Identifying Your Human Rights

As a person with a disability, you have the right to equal access to employment (Canadian Human Rights Commission), which includes workplace accommodations if needed. According to the BC Human Rights Code (n.d.):

A person must not, without a bona fide and reasonable justification, deny to a person or class of persons any accommodation, service, or facility customarily available to the public, or discriminate against a person or class of persons regarding any accommodation, service, or facility customarily available to the public because of the race, colour, ancestry, place of origin, religion, marital status, family status, physical or mental disability, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, or age of that person or class of persons (Section 8[1]).

If you feel your employer has not honored this right, you may choose to make a formal complaint. If so, make sure to document your experiences and review your company’s policy on the complaint process. Then, follow the steps required to get your complaint heard. If you need assistance with the process, contact your designated human resources officer for support.

Failing to provide accommodations, bullying, cutting hours, or letting you go for reasons related to your disability is considered discrimination. Sometimes, people unintentionally say discriminatory things. These statements are called ‘microaggressions’ and are usually subtle and can be more difficult to address. Section What Are Microaggressions will help you identify microaggressions.

It is important to understand your human rights and what to expect if your complaint is not resolved internally. You may choose to take your case to the BC Human Rights Tribunal.

Click on the links below to learn more about your rights and how to file a complaint with the Tribunal.

- BC Human Rights Code (http://www.bclaws.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/96210_01)

- BC Human Rights Tribunal (http://www.bchrt.bc.ca/)

- BC Human Rights Clinic (https://bchrc.net/)

Exercise 10.5 Identifying Your Human Rights and Complaint Process

- Identify the section in the BC Human Rights Code (https://www.bclaws.gov.bc.ca/civix/document/id/complete/statreg/00_96210_01) that describes the rights of people with disabilities. Describe your rights.

- Describe the process for filing a human rights complaint with the BC Human Rights Tribunal (http://www.bchrt.bc.ca/).

- If applicable, describe your workplace policy on the duty to accommodate employees with disabilities.

- If applicable, describe your workplace policy related to the process to file a complaint.

Exercises 10.1 to 10.6: Activity Worksheet 1-6 [PDF]

What Are Microaggressions?

In this section, we will discuss how to identify microaggressions and possible ways to address them if you find they are affecting you in the workplace. A microaggression can be subtle and/or a general use of language or behaviour that is discriminatory in nature. People who use microaggressions may not be aware that they are doing so (Nordmarken, 2014). Nevertheless, microaggressions can negatively impact different groups of people, including people with disabilities.

Examples of microaggressions:

-

People should be able to do all the physical aspects of the job, otherwise, they are not qualified.

-

A “mental health” day is just an excuse not to show up to work.

-

People probably fake their medical documentation to get perks.

-

That’s so retarded.

Microaggressions

Changing attitudes to cultivate a more inclusive workplace can be challenging. If you are comfortable doing so, you may find it helpful to speak to your co-worker(s) about how you are impacted by their words and/or behaviour. If you plan to make a formal complaint, be sure to document what you are experiencing and follow the complaint process. Make sure you are practicing self-care if you find yourself unsettled by microaggressions in the workplace.

Where Can I Get Additional Help?

Finding Resources

Community resources are a good way to access additional support related to your disability and other factors that may impact your employment success. These factors may include:

- Financial difficulties

- Difficulties finding housing

- Other health issues

- Legal difficulties

- Sexualized violence

- Racialization

- Language barriers

- Relationships with family

- Relationships with friends

- Transportation

- Lack of food resources

- See The Interactive Deep Map (https://access.trubox.ca/) from TRU, which is designed to find and list resources available in your community. This resource is for faculty members or community employers who are supporting TRU students in achieving their employment goals, or for TRU students who may be experiencing barriers to employment and are looking for helpful resources.

- Identify two resources related to your disability or health condition.

- Identify four resources related to other factors that may affect your employment.

Conclusion

Living with a condition that impacts your functioning is not always easy, especially when it comes to equitable access to employment and requesting accommodations. The information provided in this chapter is intended to provide practical tools to help you navigate a system that doesn’t always make sense. Keep your accessibility tools with your other job search documents, so that you can easily access them as needed.

Long Descriptions

Figure 10.7 Long Description

The following conditions are listed as a disability by the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction (2022, p. 9):

- Arthritis

- Asthma

- Some forms of cancer

- Chronic fatigue syndrome

- Chronic pain

- Chronic bronchitis

- Emphysema

- Crohn’s and Colitis

- Diabetes

- Epilepsy

- Fibromyalgia

- Hepatitis C

- HIV/ AIDS

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- Lupus

- Meniere’s Disease

- Multiple Schlerosis

- Migraines

- Parkinson’s Disease

- Mental health conditions

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Bipolar disorder

- Schizophrenia

- PTSD

Note. Many of these conditions are also invisible…

Back to Figure 10.7

Figure 10.8 Long Description

When we consider equity, diversity, and inclusion, accessibility equals equity. A deficit in equal access to employment for people with disabilities may intersect with other experiences of disadvantage, marginalization, and/ or privilege, such as:

- Survivors of sexual violence

- Indigenous Peoples

- LGBTQ2+

- Women

- International status

- Religion

- Socio-economic status

- Racialized status

Back to Figure 10.8

Figure 10.9 Long Description

Mont and Loeb (2010) identified the following functional impacts in the workplace (p. 165):

- Physical impacts

- Standing

- Sitting

- Stair climbing

- Fatigue

- Handwriting

- Lifting, carrying, and reaching

- Grasping, gripping, and dexterity

- Mobility

- Cognitive and Behaviour Impacts

- Attention and concentration

- Memory

- Information processing

- Stress management

- Social interactions

- Organization/ time management

- Communication

- Fatigue

Back to Figure 10.9

Figure 10.10 Long Description

Simler (2020) identified the following functional impacts, and examples of accommodations for those impacts, in the workplace:

- Standing – provide a stool or a chair

- Sitting – provide stretch breaks

- Stair climbing or lack of mobility – provide an accessible workspace

- Communication – provide an assistant or interpreter

- Fatigue – provide stretch breaks or extra time

- Handwriting or dexterity – speech to text software

- Attention or concentration – distraction-reduced environment

- Social interactions – redistribution of workload

- Information processing – provide extra time or repeat instructions

Back to Figure 10.10

Figure 10.11 Long Description

The Canadian Disability Benefits (2014) website lists the following types of disability:

- Chronic Health

- Neurological

- Mental Health

- Physical Health

- Hearing

- Visual

- Speech

- Acquired Brain Injury

- Cognitive

- Multiple

- Learning

Back to Figure 10.11

References

B.C. Human Rights Tribunal. (n.d.). http://www.bchrt.bc.ca/

Barile, M. (2002). Individual-systemic violence: Disabled women’s standpoint. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 4(1), 1–14. https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol4/iss1/1/

Brown, L. A., & Strega, S. (2015). Research as resistance: Revisiting critical, indigenous, and anti-oppressive approaches (2nd ed.). Canadian Scholars Press.

BuzzFeed Australia. (2017). What is privilege? #AustraliaDay (video). Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/watch/?v=1936578223240531

Canada Disability Benefits (2014). Types of disabilities. https://canadiandisabilitybenefits.ca/types-of-disabilities/

Canadian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.) Employer obligations. https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/employer-obligations

Canadian Humans Right Commission. (2015). The rights of persons with disabilities to equality and non-discrimination: Monitoring the implementation of the UN Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in Canada. HR4-29/2015E-PDF. https://www.chrc-ccdp.gc.ca/eng/content/rights-persons-disabilities-equality-and-non-discrimination

Centers for Disease Control and Protection (2020). Disability and health overview. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/disability.html

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press. https://www.memphis.edu/ess/module4/index.php

Florida Center for Students with Unique Abilities [FCSUA]. (2020, November 24). Integrating the social model of disability into FPCTP (video). YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Kn85fGUu5Sc

Harvey, N., Veiszadeh, M., Wray, N., & Mendoza, A. (2017, January 24). What is privilege? BuzzFeed. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.buzzfeed.com/nicolaharvey/what-is-privilege

Human Rights Code, R.S.B.C. c. 210 (1996). King’s Printer. www.bclaws.ca/Recon/document/ID/freeside/00_96210_01# (This Act is current to March 1, 2023)

Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction. (2022, June 27). Persons with disabilities designation application, HR2883 [pdf, p. 9]. Government of British Columbia. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/british-columbians-our-governments/policies-for-government/bc-employment-assistance-policy-procedure-manual/forms/pdfs/hr2883.pdf

Mont, D., & Loeb, M. (2010). A functional approach to assessing the impact of health interventions on people with disabilities. Alter, 4(3), 159–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alter.2010.02.010

Nordmarken, S. (2014). Microaggressions. TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1(1-2), 129–134. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2399812

Pardo, P., & Tomlinson, D. (1999). Implementing academic accommodations in field/practicum settings (U15925204). University of Calgary Student and Academic Services, Disability Resource Centre. https://digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/CS.aspx?VP3=DamView&VBID=2R3BXZATZ06GN&SMLS=1&RW=1920&RH=929

Piepzna-Samarasinha, L. L. (2018). Care work: Dreaming disability justice. Arsenal Pulp Press.

Robertson, J., & Larson, G. (2018). Disability and social change: A progressive Canadian approach. Fernwood Publishing.

Simler, C. (2020, July 9). 30 examples of workplace accommodations you can put into practice. Understood.org. https://www.understood.org/en/articles/reasonable-workplace-accommodation-examples

Statistics Canada. (2017). New data on disability in Canada, 2017. Government of Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2018035-eng.htm. Use of this publication is governed by the Statistics Canada Open Licence Agreement.

Stroman, D. F. (2003). The disability rights movement: From deinstitutionalization to self-determination. University Press of America.

University of Memphis. (n.d.). Module 4: Asset based community engagement. U of M’s Urban-Serving Research Mission. https://www.memphis.edu/ess/module4/

Washington, E. F. (2022, May 10). Recognizing and responding to microaggressions at work. Harvard Business Review. hbr.org/2022/05/recognizing-and-responding-to-microaggressions-at-work

World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF) external icon. WHO. http://www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/

Media Attributions

- Figure 10.1 New Data on Disability in Canada, 2017 [adapted] by Statistics Canada [archived content], used under the Statistics Canada Open Licence Agreement. This does not constitute an endorsement by Statistics Canada.

- Figure 10.2 By author, adapted from Disability and Health Overview, Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Umbrella Rain Red Weather Campbell valley [vector graphic] by OpenClipart-Vectors/27376, on Pixabay.

- Figure 10.3 By author, adapted from information from Pardo and Tomlison (1999). Medical model and social model diagram [12:50] by FCSUA (2020) on YouTube.

- Figure 10.4 By author. Labyrinth Maze Wall [vector graphic] by OpenClipart-Vector/27376, on Pixabay.

- Figure 10.5 By author. Road Sign Roadsign No Prohibited Forbidden Delete [vector graphic] by OpenClipart-Vector/27376, on Pixabay.

- Figure 10.6 By author. Labyrinth Maze Wall [vector graphic] by OpenClipart-Vector/27376, on Pixabay; Road Sign Roadsign No Prohibited Forbidden Delete [vector graphic] by OpenClipart-Vector/27376, on Pixabay.

- Figure 10.7 By author. Information from the Ministry of Social Development and Poverty Reduction (2022, p. 9)

- Figure 10.8 By author.

- Figure 10.9 By author. Information from Mont and Loeb (2010, p. 165)

- Figure 10.10 By author. Accommodation photograph by __, on Pixabay. [I cannot find this picture on Pixabay – see Google doc]

- Figure 10.11 By author. Information from Canadian Disability Benefits, (2014)

- Figure 10.12 By author. Woman Standing Hand Hips Young [vector graphic] by MoteOo/134 Bilder, on Pixabay.