2. Labour Market Information

Larry Iles

Introduction

Why Won’t the Baby Boomers Leave the Canadian Labour Market?

At the time of writing this chapter, Canada is beginning its recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. How the world of work will adjust to the post-pandemic world remains to be seen. By now, readers may have seen web-based articles discussing the “Great Resignation.” Broadly, this term refers to the number of workers that have not returned to their pre-pandemic jobs. The internet is filled with articles on this topic, with titles like “Who is Driving the Great Resignation?” (Cook, 2021) and “The Great Resignation Rages On” (Leonhardt, 2022). However, it is too early to tell where these displaced workers have gone and the types of new jobs they may have found. In this age of media, it is difficult to determine reliable sources of information. One reliable source is Labour Market Information (LMI), which helps students and new graduates navigate the world of work and potential career pathways. LMI provides a vast amount of data and information that can assist students in both career planning and job searches. LMI can be used to check on job growth, economic climates, skills needed, wages, labour supply and demand, and peering into the future. According to the Business Council of Canada (Drummond & Halliwell, 2016), students can also use LMI to understand how their educational credentials will be “measured, accredited, and transferred.” With the advent of easy access to LMI, there is no lack of labour market information. Yet the information can be scattered and is offered by a variety of sources. This chapter will highlight a small subset of the information available and show how this information can be utilized for career development and job searching.

Learning Objectives

After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to:

- Understand the current labour market conditions in Canada using population statistics.

- Identify and reflect on career choices through labour market research.

- Create a career analysis using labour market research.

Who am I?

Current Labour Market Conditions in Canada Using Population Statistics

Let’s begin with a brief review of the population cohorts that affect the labour market in Canada. First, the “Baby Boomers.” This group is still in the labour force and, due to positive changes in health and removal of mandatory retirement, it is not exiting as early as some predicted. For current students, this is relevant because Baby Boomers are still working, and in some cases holding onto jobs in careers that students are applying for. In Canada, the Baby Boomers continue to be active in the labour market. According to David Foot (2007), the number of working-age Canadians older than 45 represents 42% of the labour market. That means that over 7.5 million Canadians aged 50–64 (Statistics Canada, 2016) are potentially still in the labour market. The actual dates for the Baby Boomer demographic are debatable; however, the trend places Baby Boomers as those born between 1947 and 1966 (Foot, 2007). The oldest Baby Boomers are in their early 70s; the youngest in this cohort are in their early 60s. This group represented approximately 10,000 million live births for this period. The cohort is typically defined as one that did well economically and was part of a North American post-WWII boom that stretched into the 1980s. The point is that Baby Boomers will occupy space in the labour market well into the late 2020s. This may affect students graduating into sectors or careers that typically do not see rapid change in job growth.

The next group in the labour market is called “Generation X.” Douglas Coupland used this term in his 1991 book, Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. This generation represents approximately 5.4 million Canadians born between 1965-1980. They generally have higher educational attainment than the boomers, have seen an increase in competition for jobs, and have more geographic career mobility.

The next largest labour market cohort is the “Millennials” (Strauss & Howe, 1992). This group is the subject of volumes of media dissection. Generally, Millennials are defined as highly educated; tending to remain at the family home longer than previous cohorts; they are experiencing a harder time entering the labour market due to the large baby boom generation that came before them. Millennials are characterized as embracing new lifestyle trends and being spenders. This group represents over 7 million live births in Canada between 1980 and 1995, and is a major group in the labour economy of Canada. It is predicted that Millennials will comprise three-quarters of the world’s workforce by 2025 (Lyons, 2016).

Canada is not unique in naming this population group. Other countries refer to Millennials as the Curling Generation (Norway); ken lao zu — the generation that eats the old (China); Generacion ni ni — no work/ no study (Spain); Generation Y (Australia); and Generation Rent (UK) (Lyons, 2016).

Lastly, in Canada there is “Generation Z.” Figure 2.1 depicts the major characteristics of this cohort, as listed by Talent Ladzima (2018) which represents over 6 million born since 1996. The oldest of these are now entering the labour market.

Generation Z: A New Generation has Arrived.

For students getting close to graduation, it is important to think about these numbers when researching careers, and to consider the future labour force growth or decline in one’s planned career choice. For example, at a small university in British Columbia, there are two full-time career counselors, both with 10 to 20 years remaining in their careers. If a student were planning on a career in this sector in this location, they would still have a long wait for the Baby Boomer and a Millennial to exit the labour force. The other consideration for this data is that new graduates will face the phenomenon of having four generations in the workplace — each with its unique workplace worldview. How new graduates interact with other generations remains a factor for organizations deciding on team fit and organizational communication structures. This topic is covered in subsequent chapters.

Labour Market Information (LMI)

Employers often inform post-secondary career counsellors that they are concerned about candidates’ lack of knowledge about the industry to which they are applying. Students not only need to research the job and company, but also understand the issues the sector is experiencing, the drivers of the sector, and the future for the sector. This information is invaluable when writing a cover letter and preparing for interviews — especially for the question, “What is your future career plan?” It is crucial to find relevant and reliable LMI when researching careers and applying for jobs. Students can use any of the following key sites to build their LMI knowledge. Ideally, students will begin this type of research long before graduation to assist with both academic and career decisions.

What Matters to Canadian Youth?

Use of LMI for Career Planning

There are many career development labour market sites available to students. This section will focus on two key sources of LMI for career planning. One highly recommended report is the British Columbia Labour Market Online published by Christian Saint Cyr. The highly informative site provides easy-to-review labour market information. Another recommended resource is produced by the Labour Market Information Council (LMIC). This resource reflects the scope of the Canadian labour market. For students and new graduates, it provides access to career decision-making data. Students can use these sites to determine where the jobs are, skills and credentials needed, projected growth of an industry — even geographical locations of career choices. For example, students can access a report produced in British Columbia by Labour Market Solutions (http://labourmarketsolutions.ca/). Their monthly newsletter focuses on different career choices and provides LMI for that area. For example, one issue on midwives provided information on education, the number of midwives in BC, a review of the typical workload, possible job descriptions, and future growth. These and additional resources are listed near the end of this chapter. Students can use this information to prepare a career plan academically and post-graduation.

The focus of this section of the chapter will be the use of LinkedIn (https://ca.linkedin.com/) as a source of labour market data. LinkedIn provides students with a vast amount of information — if they are willing to work a little harder to gather it. According to LinkedIn, there are over 17 million Canadian users with over 30 million global companies on the platform. Recently, LMIC partnered with LinkedIn to summarize over 400,000 paid job vacancies. Their summarized data provides the top required skills and top job titles across 10 major cities. The results showed that common skill groups such as business management, leadership, and oral communication were required skills for all students and new graduates. This is not surprising because these skills often surface in “Top 10 Career Skills” lists. However, it shows students which skills to highlight in application packages and interviews.

Another way to use LinkedIn for LMI and career planning is by reverse engineering profile information. The main challenge students have is how to determine the type of entry-level position for their career immediately following graduation. Using informational interviews is one method to gain insight into person’s career progression. However, they are time-consuming and limited to a small cross-section of professionals. LinkedIn profiles can (depending on the details included) provide similar information to that gained in an information interview but on a much larger scale. Students investigating possible career paths can search LinkedIn by degree type. For example, a student wondering about the career progression offered by a Bachelor of Arts (BA) Degree in Psychology can search for this degree type. Results will show all LinkedIn members that have indicated this degree in their profile. Depending on how complete the profile is, students will be able to determine the first position the degree holder obtained and observe the career progression following graduation. If a student were to review 50 BA/psychology profiles, a pattern would emerge for education, additional training, job titles, and potential employer organizations. Students could reflect on this information in terms of interests, academic planning, and future career roles for this degree type.

Watch the following video, Reverse Engineer LinkedIn for Labour Market Information, by Larry Iles (2022) on YouTube, for an example of how to use LinkedIn for LMI.

Using LMI for Skill Gap Reflection

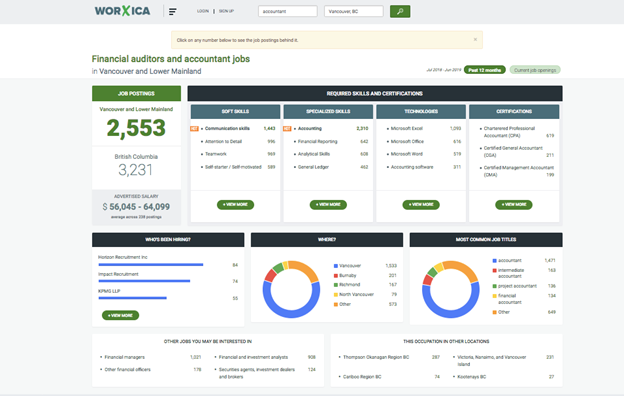

Financial Auditors and Accountant Jobs in Vancouver and Lower Mainland

In the example from Worxica, shown in Figure 2.3, an accounting student can determine the skills graduates need to be an accountant in Vancouver, B.C. and begin to reflect on methods to gain these skills prior to graduation. Students can also use this LMI tool to build their skill section in resumes and cover letters and to prepare for interview questions.

Industry 4.0 and the Labour Market

Industry 4.0 refers to a significant transition in the digitization of manufacturing. However, the transition goes far beyond the world of manufacturing. The expansion of Industry 4.0 will be the digitation of work in many roles and sectors. Technological changes in labour markets are nothing new, and the question remains: Does increasing digitization technology (tech) and automation always lead to job loss? Will artificial intelligence (AI) cause the removal of the human element in the labour market? The nineteenth-century economist Frédéric Bastiat (1850) wrote on the concept of what is seen, and what is not seen. To paraphrase, he was concerned that society loses if things of value are “uselessly destroyed” (for the purpose of this chapter, jobs). Bastiat discussed how the loss of labour in an economy can be a destructive force without a thoughtful approach to the consequences. Bastiat suggested machines don’t take away jobs; they free people up for different jobs.

Will AI take over the majority of jobs in the world? Some predict it will, and others predict it will not. The latter include the Fraser Institute (2019), Carden (2017), and the World Economic Forum (2022). However, Facebook (now Meta) CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Tesla founder, Elon Musk (Clifford, 2017), have been vocal in their belief that AI — systems that perform a single task — or artificial general intelligence (AGI) — systems that perform a range of tasks and solve a range of problems — will result in unemployment. After all, AI and AGI can be programmed to complete any task a human can. Yet, there is evidence that technology does not reduce labour market opportunities. According to the World Economic Forum (2022), despite 80% of labour having been on farms in the 1800s, as labour markets have expanded over the past 200 years, only 2% of jobs are now related to farming in Canada. However, the economy added over 700,000 jobs in Fall 2021 and Winter 2022 (Statistics Canada, 2022). Of course, the reality is that technology has affected labour markets and increased positions in many occupations, as evidenced by the high demand for workers in the computing science fields (Labour Market Information Council, 2022). But what are the ramifications for the broader labour markets over the next 50 years?

Students are advised to be cautious about making all their career decisions based on possible future work increases. Elements such as the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2008 global recession can disrupt even the best LMI predictions. Chaos theory teaches that the farther a prediction extends, the more probability that prediction may collapse. However, the world is experiencing a massive technical shift as it moves into the third decade of the millennium. We will briefly explore the possible effects on labour markets, job losses, and job gains.

Mokyr (2018) argues that tech advancement does not mean job loss. Certainly, the industrial revolution replaced some roles. The tech change, however, created new sectors and increased employment: mechanics to fix machines, supervisors to coordinate mass-production factories, financial workers to manage the increased globalization of goods, and so on. What seems consistent is that it is easy to replace lower skill jobs with technological change, and harder to replace jobs that complement technology. Roles that require empathy, creativity, and initiative will still be required (Carden et al., 2019).

What jobs could be replaced? Elon Musk (Collinson, 2017), Mark Zuckerberg, and Bill Gates suggest half of all current employment could be replaced by AI — and that AI will lead to massive labour market disruption. In a Wall Street Journal article, Carl Benedikt Frey (2019) predicts that AI will destroy more jobs than it creates. He argues that over the past 200 years, technology has replaced many workers — especially in jobs that do not need advanced skills or training. Dr. Brian Goldman (2019), the CBC host of “White Coat, Black Art,” speaking at the Common Voices Lecture Series at Thompson Rivers University on February 17, 2019, said that the future of work will advantage jobs that involve thinking, not doing.

So, what can LMI tell us about the future of jobs? A reviewing of employment records over the past 10 years suggest that, arguably, this is the period when tech and AI have been increasing at a rapid pace. However, the Labour Market Information Council (2018) reports a steady increase in the labour market, not a decline. The US is entering its twelfth year of steady job increases — regardless of the advent of AI and AGI. The World Economic Forum report (WEF, 2022) predicts 50% of current rote-type labour can be replaced by machines and AI. In some fields, this is already happening. The food delivery and restaurant industry have been forever altered due to apps like Door Dash and Skip the Dishes. There are reports that law firms may need fewer junior lawyers as there are AI programs that can search case law and prepare case arguments. Typically, it was the law articling students and new lawyers that conducted this work. The key consideration for students when using LMI for decision-making and determining the future of technology is to reflect on this question: Can a mechanical or AI application be developed that would replace my core skill set?

At the time of this writing, every person is feeling the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. The loss of labour and the movement of labour is occurring on a vast scale. There has been the loss of jobs in some sectors like the tourism sector, typically made up of youth and lower-wage employees, but also job gains in the finance, supply chain management, and IT sectors. The pandemic highlighted sectors that were more vulnerable to labour market shifts and the use of technology. Students using LMI information as part of their career plans will be better prepared if they stay current with the shifts in the job market economy. LMI research alerts students and new graduates to potential shifts and disruptions in the job market. Students who pay attention to LMI will be better able to cope with the ultimate shifts in their chosen occupation. Prepared students will not say, “I didn’t see that coming” following layoffs due to tech or other factors.

Activities

Exercise 2.1 Could You Be Replaced by an App?

Based on your LMI research from this chapter into your future career — going back to the WorXica.com platform discussed in using LMI for Skill Gap Reflection— reflect on which skills from jobs posted in your future career choice over the past months could be replaced by realistic AI or AGI applications. What elements of your role could be performed by an app? How easily could this app be developed? What might this app be called?

Exercise 2.2 Career SWOT – Identify External Opportunities and Career Gaps

A key tool in the strategic planning process, SWOT can also be applied to career planning.

This tool is an LMI marketing analysis using the SWOT technique. A SWOT analysis focuses on internal and external environments, examining strengths and weaknesses in the internal environment and opportunities and threats in the external environment.

Imagine your SWOT analysis to be structured like the following table. To construct your SWOT analysis to set a course for your career planning, examine your current situation. Using LMI:

- What are your strengths and weaknesses?

- How can you capitalize on your strengths and overcome your weaknesses?

- Are there career gaps that could be addressed before graduation?

- What are the external opportunities and threats in your chosen career field?

Table 2.1 A: SWOT analysis – Internal Strengths and Weaknesses

| INTERNAL STRENGTHS | INTERNAL WEAKNESSES |

|---|---|

Internal positive aspects that are under your control on which you plan to capitalize:

|

Internal negative aspects that are under your control on which you plan to improve:

|

Table 2.1 B: SWOT analysis – External Opportunities and Threats

| EXTERNAL OPPORTUNITIES | EXTERNAL THREATS |

|---|---|

Positive external conditions that you do not control that you can plan to take advantage of:

|

Negative external conditions that you do not control, but the effects of which you may be able to lessen:

|

Resources

- British Columbia Labour Market Online (https://www.labourmarketonline.com/)

- Business Council of Canada (https://thebusinesscouncil.ca/)

- Canada Sector Councils (https://www.job-link.ca/Canada_Sector_Councils.html)

- Fraser Institute (https://www.fraserinstitute.org/tags/canadian-labour-market)

- Glassdoor (https://www.glassdoor.ca/Job/vancouver-accountant-jobs-SRCH_IL.0,9_IC2278756_KO10,20.htm)

- Labour Market Information Labour Market Information Council (LMIC) (https://lmic-cimt.ca/)

- Labour Market Solutions (https://www.cfeebc.org/resourcepublishers/labour-market-solutions/?doing_wp_cron=1665013774.3195691108703613281250)

- Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey (LFS) (https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=3701)

- World Economic Forum 2022 (https://www.weforum.org/?src=DAG_2&gclid=CjwKCAjwm8WZBhBUEiwA178UnDEZFoq669CK7_8G4wgWLgwN8Krydqb78HIoGSgYRW7ZUjgdkgeA1BoCvbIQAvD_BwE)

- WorXica (https://worxica.com/)

Long Descriptions

Figure 2.1 Long Description

According to Mariana von Jörg (2017) at Engarde, “Digital Natives” born after 1995:

- express themselves with their own style,

- tend to travel more,

- demand 24-hour access,

- [were] born to swipe,

- [use] video messages more than texting, and

- [are] masters of social media.

References

Bastiat, F. (1850). That which is seen, and that which is not seen. http://bastiat.org/en/twisatwins.html

Carden, L., Maldonado, T., Brace, C., & Myers, M. (2019). Robotics process automation at TECHSERV: An implementation case study. Journal of Information Technology Teaching Cases. 9(2), 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043886919870545

Clifford, C. (2017, July 17). Elon Musk: Robots will be able to do everything better than us. CNBC.com. https://www.cnbc.com/2017/07/17/elon-musk-robots-will-be-able-to-do-everything-better-than-us.html

Cook, I. (2021, September 15). Who is driving the great resignation? Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/09/who-is-driving-the-great-resignation

Coupland, D. (1991). Generation X: Tales for an accelerated culture. St. Martin’s Press.

Frey, C. (2019, October 21). The high cost of impeding automation. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-high-cost-of-impeding-automation-11571958240

von Jörg, M. (2017, June 1). Introducing: Generation Z (digital image). Kompetenz. En Garde. https://web.archive.org/web/20200808003220/https://www.engarde.net/introducing-generation-z/#.Xy3yl3bP1D8

Drummond, D., & Halliwell, C. (2016). Labour market information: an essential part of Canada’s skills agenda. Business Council of Canada. https://thebusinesscouncil.ca

Goldman, B. (2019, Feb 17). Will someone please invent an app for that? Common Voices Lecture Series. Thompson Rivers University Student Union (TRUSU),. Kamloops, BC. https://trusu.ca/campus-life/common-voices/

Hill, T. (2022, September 13). A closer look at Canada’s changing labour market. Fraser Institute. https://www.fraserinstitute.org/blogs/a-closer-look-at-canadas-changing-labour-market

Howe, N. & Strauss, W. (1992). The new generation gap. Atlantic-Boston, 270, 67–67. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1992/12/the-new-generation-gap/536934/

Iles, L. (2022, Mar 24). Reverse engineer LinkedIn for labour market information [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IW08f6D33aE

Kadzima, T. (2020, July 3). Generation Z: A new generation has arrived . LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/generation-z-new-has-arrived-talent-kadzima

Labour Market Information Council (LMIC). (2018). The future of work in Canada: Bridging the gap. LMI Insights, (2), 1–8. https://lmic-cimt.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/LMI-Insights-Issue-2-EN.pdf

Leonhardt, M. (2022, January 4). The great resignation rages on as a record 4.5 million Americans quit. Fortune Magazine. https://fortune.com/2022/01/04/great-resignation-record-quit-rate-4-5-million/

Lyons, K. (2016, March 8). Generation Y, curling or maybe: What the world calls millennials. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/08/generation-y-curling-or-maybe-what-the-world-calls-millennials

Mlynek, A. (2007). 2020 Demographics: The human factor. An interview with David Foot [PDF]. Canadian Business, 80(20), 23–31. Footwork.com. http://www.footwork.com/canbus.pdf

Mokyr, J. (2018). The past and the future of innovation: Some lessons from economic history. Explorations in Economic History, 69, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2018.03.003

Statistics Canada. (2019). A portrait of Canadian youth. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2019046-eng.htm

Statistics Canada. (2017). 2016 Census of population. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/index-eng.cfm

von Jörg M. (2017). Introducing: Generation Z [image]. En Garde.

https://www.engarde.net/introducing-generation-z/

World Economic Forum. (2022). Reskilling revolution: Preparing 1 billion people for tomorrow’s economy. https://www.weforum.org/impact/reskilling-revolution-preparing-1-billion-people-for-tomorrow-s-economy/

Media Attributions

- Figure 2.1 Introducing: Generation Z by Mariana von Jörg (2017) via En Garde.

- Figure 2.2 A Portrait of Canadian Youth by Statistics Canada (2019) is used under the Statistics Canada Open Licence Agreement.

- Figure 2.3 Financial Auditors and Accountant Jobs in Vancouver and Lower Mainland, WorXica (2019) – Used with permission.