4. Volunteering and Experiential Learning

Brad Harasymchuk

Introduction

Volunteering has many benefits to you and your community. Most likely, you have already volunteered your time and helped others on many occasions and in many different ways. What you may not be aware of are the many skills that you may develop while volunteering. This chapter will give you an overview of the what, why, and how to volunteer. It will also provide a list of skills you can develop — but it will be your responsibility to prioritize the skills you would like to develop. The chapter concludes with an activity that allows you to create a Volunteer Action Plan for engaging in your next volunteer experience. Let’s get started!

Learning Objectives

After carefully reading this chapter, completing the exercises within it, and answering the questions at the end, you should be able to:

- Recognize that volunteering can enhance your career development.

- Identify skills associated with volunteering.

- Develop a Volunteer Action Plan to engage with your next volunteer experience.

What is Volunteering?

Volunteering can be broken down into two categories: managed and unmanaged. As Dingle et al. (2001) explain, managed volunteering takes place in public, private, and not-for-profit organizations, while unmanaged volunteering is spontaneous and sporadic help between members of the public, or family and friends. This chapter will focus more on managed volunteer experiences, and more specifically within non-profit organizations. However, this should not take away from your efforts in seeking out unmanaged volunteering experiences in your community.

Volunteering has been defined as, “unpaid help, in the form of time, service or skills, through an organization or group, and carried out willingly without coercion” (Oppenheimer, 2008, p. 6). It is really about you going out and helping at a not-for-profit organization. See Appendix A: Places to Volunteer in Your Community for a list of community organizations in which you may be able to volunteer.

Communities rely on volunteers to serve and help. Canadians volunteer over 1.9 billion hours a year which is significant (Statistics Canada, 2013). The Conference Board of Canada (2018), estimates that volunteering would add nearly 56 billion dollars to Canada’s Gross Domestic Product in 2017 alone, which would account for 2.6% of Canada’s economic activity. This truly shows the impact of volunteering, but why do people give their time to help out in their communities? Let’s explore some reasons why so many Canadians volunteer.

Why Volunteer?

There are multiple reasons why people volunteer. Some people volunteer solely to benefit other people or a cause, and this is known as altruism. Others volunteer to meet people, socialize, and feel good about doing something good for their community, which may be done for personal well-being. A practical reason to volunteer is to gain valuable skills to use both personally and professionally towards your career development. Table 4.1 created by Smith, Holmes, Haski-Leventhal, Cnaan, Handy, & Brudney (2010), outlines the top motivations for students who volunteer. The following sections will elaborate on these and other reasons to get out there and volunteer.

Table 4.1

Motivations to Volunteer

| Motivation for Volunteering | Motivational Item | Regular Volunteers (%) | Occasional Volunteers (%) | Non-Volunteers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumental/ Career-Related | To post of CV (resume) when applying for a job** | 61.5 | 65.1 | 70.6 |

| Instrumental/ Career-Related | To put on CV (resume) for admission to higher education ** | 58.0 | 61.5 | 67.0 |

| Instrumental/ Career-Related | To make new contacts that might help a business career ** | 57.7 | 56.5 | 62.0 |

| Instrumental/ Career-Related | To help one get a foot in the door for paid employment N.S. | 58.2 | 57.6 | 60.7 |

| Altruistic/ Value-Driven | It is important to help others ** | 90.2 | 85.7 | 79.2 |

| Altruistic/ Value-Driven | To work for a cause that is important ** | 87.8 | 84.0 | 78.3 |

| Altruistic/ Value-Driven | Makes one feel better * | 75.4 | 71.6 | 68.0 |

| Altruistic/ Value-Driven | Volunteering gives one a new perspective ** | 79.0 | 72.9 | 64.3 |

| Altruistic/ Value-Driven | To learn about the cause ** | 63.7 | 57.1 | 55.9 |

Note. † Volunteers: Why do you volunteer? Non-Volunteers: Why do you think people volunteer? Percentage of respondents strongly agreeing or agreeing. ** Significant at the 0.01 level. *Significant at the 0.05 level. N.S. Not significant. (Smith et al., 2010). Used under CC BY 3.0 [Adapted: Recreated for this format and part of original table removed.]

Altruism and Empathy

Altruism is a commendable reason to volunteer with organizations. “Altruism refers to helping others when there is little or no perceived potential for a direct, explicit reward to the self” (Carlo et al., 2003, p. 113). The primary focus is on the ‘other,’ whether it be human, animal, or social cause. As shown in Table 4.1, the number one motivation for students to volunteer was to “help others.” This is a true altruistic endeavor, but it does not mean it is the only reason to volunteer. Let’s now look at increasing our well-being as a motivation for volunteering.

Personal Well-being

Research has shown that prosocial activities, including volunteering, contribute to the constructs found within well-being (Li & Ferraro, 2005; Thoits & Hewitt, 2001). Volunteer experiences offer a space for you to develop your well-being, but this can be different for each individual, as personal well-being means different things to different people. Thoits & Hewitt (2001), found that volunteering enhances well-being in six areas, including: happiness, life satisfaction, self-esteem, sense of control over life, physical health, and overcoming depression. Well-being seems like a valid reason to volunteer, but be aware that taking on too many responsibilities, including volunteering, can cause you to become over-extended, which can actually lead to being unwell. So, if you can enhance your well-being while volunteering, what else can you gain while helping in your community? Let’s take a look at developing new skills while volunteering.

Skill Development

Altruism and enhancing your well-being are compelling reasons to volunteer, but focusing on skill development can lead to learning that transcends other areas in your life. It can be as easy as picking a skill and intentionally focusing on developing that skill while volunteering. For example, maybe you want to focus on teamwork. While volunteering, you may want to ask questions to some team members about how they work together or whether they follow a particular theory or philosophy of teamwork. You may want to think about how ideas around teamwork differ or are similar to how you work as part of a team. These are only examples, but the most important aspect of skill development is being intentional about building a skill and focusing on it throughout your volunteering experience. There are many skills you can develop as a volunteer. Table 4.2 recommends 19 skills that young people reported developing while volunteering (Oldfield, 2006). Take a look and see what skills you might develop during your next volunteer experience. See Career Planning and Goal Setting for more information on skills development.

Table 4.2

Skills and Characteristics Developed While Volunteering

| Skills and Characteristics |

|---|

| Confidence |

| Communication |

| Teamwork |

| Managing relationships |

| Understanding society |

| Self-management |

| Preparation for work |

| Active listening |

| Leadership |

| Taking responsibility |

| Improved learning |

| Decision-making |

| Understanding diversity |

| Self-awareness |

| Problem-solving |

| Rights and responsibilities |

| Planning |

| Negotiation |

| Budgeting |

Another useful skill to develop while volunteering is networking. Networking can be defined as a “goal-directed behavior that occurs both inside and outside of an organization, focused on creating, cultivating, and utilizing interpersonal relationships” (Gibson et al., 2014, p. 146). Also, see Job Search Strategies, for more information on networking. When volunteering, you have the opportunity to create relationships with other volunteers. You likely already have a commonality with those people in that you are volunteering for the same organization. You never know who you are volunteering with; they could be your next employer or somebody who can write you a valuable reference letter. Be aware of who you are volunteering with, but don’t be presumptuous with what you want. It takes time to build relationships.

Now that you have at least three reasons to volunteer, let’s look at how to find that next volunteer experience.

How to Volunteer?

The following section will not only help you find the right volunteer experience, but will also help you get the most out of your experience. If you require accommodations for your volunteer experience due to a disability or a health condition, see Experience More Access for information on how to navigate the process. After reading this section, check out the Volunteer Action Plan that will help you during your volunteer experience.

Finding the Right Experience

The following is a quick, step-by-step guide to help you find your next volunteer experience:

-

Find a volunteer organization with which you share common interests.

It’s important to think about the skills you already possess, and your interests, to find an organization that will be a good “fit” for you. This will keep you engaged and encourage you to continue your work with the organization. For example, if you are interested in animals, you may want to contact the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (SPCA).

-

Look online or talk with friends and family to find opportunities.

You will find many volunteer opportunities online, such as Volunteer Canada (https://volunteer.ca/), or check with your local volunteer centre that can be found in most communities. Also, check with family and friends about any opportunities they may know about in your community. See Appendix A: Places to Volunteer in Your Community for a list of community organizations you may want to volunteer with in your own community.

-

Pick an organization that will help you develop new skills.

You may bring many skills to an organization, but be mindful of the skills that you may develop there. Many organizations offer training and professional development for their volunteers.

-

Manage your time.

It is important that you are able to manage all the responsibilities in your life. Although volunteer work is unpaid, consider it similar to a job or class, requiring the same commitment. Volunteer organizations rely heavily on their volunteers. Be realistic about how much time you have to volunteer, and try not to overcommit. See Preparing for Your First Professional Position for more information on time management.

-

Be aware of on-site training and requests for criminal record checks.

Some volunteer organizations will offer on-site training. Be sure to take advantage of any required training offered, and be willing to take more training if needed. You may also gain certification for certain training. This will help build your skills and develop your resume. Some organizations will request a criminal record check before you can volunteer. This is normally done if you are working with “at-risk” populations, including children or vulnerable adults. In Canada, every province is different, so be sure to look into this well in advance, as some criminal record checks can take several weeks to complete. There may also be a fee associated with criminal record checks, and some volunteer organizations will pay the fee for you. Be sure to find this out before you start the criminal record check process.

Getting the Most from Your Experience

Once you have found an organization that interests you, follow these steps to get the most from your experience:

-

Contact the organization.

The first contact with a volunteer organization is important! It is a time to ask any questions you may have, but also a time for the organization to find out about you. Some organizations expect you to contact them in person, phone, or email, while other organizations will have you fill out a questionnaire (possibly online). Each organization is different, but don’t hesitate to contact as many organizations until you find the right fit.

-

Expectations.

Every volunteer experience will be different, but if you treat volunteering like a job or class, you will have more success. Always ask what is expected of you, and be sure to communicate what you can offer the organization in terms of time and resources. Communication is key when working with organizations, as they rely on you to be a committed member of their team.

-

On the day.

Be on time! If you are unable to volunteer for some reason, contact your volunteer coordinator or supervisor in advance and let them know. They are relying on you to help on the day. When volunteering, if you don’t know something, ask for help. And finally, have fun, remember to focus on developing your skills, and network!

-

Receiving feedback.

It’s really important to ask your volunteer coordinator or supervisor for any feedback they have about your involvement in their organization. This will help you the next time you are volunteering. It is also important to take some time and reflect on your experience, which will be discussed in the next section.

Taking your Volunteer Experience to the Next Level Through Reflection

The following section will outline the use of reflective practice to be used alongside your volunteering experience. Reflection accentuates your experiences and allows for more meaningful learning to take place. Let’s see how reflection can become part of your next volunteer experience.

What is Reflection?

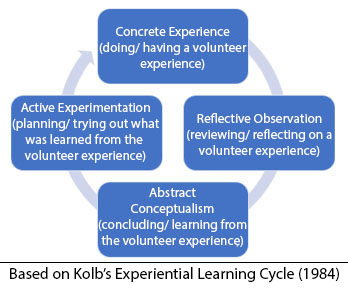

As one of the pioneers of reflective practice, John Dewey (1933), defined reflection as, “active, persistent, and careful consideration of any belief or supposed form of knowledge in the light of the grounds that support it and the further conclusion to which it tends” (p. 9). In your volunteer experience, this means being intentional about the skills you are developing and reflecting upon your experience once you are done. This process is what David Kolb (1984) developed and named the “Cycle for Experiential Learning,” as outlined in Figure 4.1.

Experiential Learning

When the experiential cycle is modeled through a volunteer experience, the concrete experience is the actual volunteer experience. When you move into reflective observation, you need to be reflective about your experience. Reflection is not about describing your experience, but more about unpacking the learning that came from the experience. It’s engaging with the sensory experiences that come from volunteering or asking critical questions about your experience. Check out Section 3 of the Volunteer Action Plan for examples of critical reflective questions. The next stage in the model is abstract conceptualization; this is the new learning that takes place through your reflective practice, which can include new skills, ideas, or concepts. This is why it is imperative that you are intentional about the skills you are developing. The final stage is active experimentation, whereby you take your new learning and adapt it to a new experience. This may be taking a new skill you learned and transferring that skill to your classes, work, or your next volunteer experience. The cycle is continuous and can be used with any experiential learning opportunities. Reflection is truly where your learning comes full circle. Let’s now look at how you can take all this information and create a plan for your next volunteer experience.

Volunteer Action Plan

The Volunteer Action Plan provided below is meant to be used before, during and after your volunteer experience. Section 1 of the plan outlines the demographic information that may be needed when selecting a volunteer experience, including when, where, and who you are volunteering with. It will allow you to keep track of any email addresses or phone numbers you may need.

Section 2 outlines the reasons you are volunteering and any skills you would like to develop while engaging in your experience. This is where you need to be intentional about the learning that can take place. This may change once you are involved in your volunteer experience, as you may not be able to work on a skill that you have outlined, and your experience may not accommodate that learning at that time. So be flexible, and choose another skill that may be more appropriate.

Section 3 is meant to be completed after your volunteering experience. This is the descriptive and reflective component to your plan. Take a bit of time and describe your experience: What were some of your duties, and what did you accomplish? Finally, answer as many of the reflective questions provided as you can. This is an important step in your learning. Get to the heart of the learning that has taken place, and be sure to be reflective.

Volunteer Action Plan PDF Version

Conclusion

Well done! You made it to the end and now have a better understanding of volunteering and its many components. The previous sections have taken you from the beginning of understanding volunteerism right through to finding an opportunity, creating a Volunteer Action Plan, and finally reflecting upon your experiences. It is now up to you to take this information and put it into action. Go out and find that opportunity to help your community and build those valuable skills that you can use in your life.

Long Description

Figure 4.1 Long Description

The following four stages are presented in a circle format with one stage moving to next then back to first stage.

- Concrete Experience (doing/having a volunteer experience)

- Reflective Observation (reviewing/ reflecting on a volunteer experience)

- Abstract Conceptualism (concluding/ learning form the volunteer experience)

- Active Experimentation (planning/trying out what was learned from the volunteer experience)

References

Carlo, G., Hausmann, A., Christiansen, S., & Randall, B. (2003). Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of prosocial tendencies for adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 23(1), 107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431602239132

The Conference Board of Canada. (2018, April). The value of volunteering in Canada [PDF]. Volunteer Canada. https://volunteer.ca/vdemo/Campaigns_DOCS/Value%20of%20Volunteering%20in%20Canada%20Conf%20Board%20Final%20Report%20EN.pdf

Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. Heath and Co Publishers.

Dingle, A., Sokolowski, W., Saxon-Harold, S., Smith, J.S., & Leigh R. (2001). Measuring volunteering: a practical toolkit [PDF]. A joint project of INDEPENDENT SECTOR and United Nations Volunteers. http://www.toolkitsportdevelopment.org/html/resources/DA/DADD6C80-1572-442B-867F-A032B970C9E2/measuring%20volunteering%20Toolkit%20UN.pdf

Gibson, C., Hardy III, J., & Buckley R. (2014). Understanding the role of networking in organizations. Career Development International, 19(2), 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-09-2013-0111

Kolb, D. (1984). Experiential learning : Experience as the source of learning and development. Prentice-Hall.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in Social sciences. Harper & Row.

Li, Y., & Ferraro, K. (2005). Volunteering and depression in later life: Social benefit or selection processes? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(1), 68–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/002214650504600106

Oldfield, C. (2006, October). Young people’s volunteering and skills development. e-Volunteerism – A journal to inform and challenge leaders of volunteers. http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/6643/1/RW103.pdf

Oppenheimer, M. (2008). Volunteering: Why we can’t survive without it. UNSW Press. Available at TRU Library with login and password. https://ezproxy.tru.ca/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=cat03106a&AN=tru.a886244&site=eds-live

Smith, K., Holmes, K., Haski-Leventhal, D., Cnaan, A., Handy, F., & Brudney, L. (2010). Motivations and benefits of student volunteering: Comparing regular, occasional, and non-volunteers in five countries. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 1(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjnser.2010v1n1a2. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Statistics Canada. (2013, April 15). Volunteering and charitable giving in Canada. Canadian Government. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/89-652-x/89-652-x2015001-eng.htm

Thoits, P. & Hewitt, L. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42(2), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090173

Volunteer Canada. (n.d.). Homepage. https://volunteer.ca/

Media Attributions

- Figure 4.1 Experiential Learning Cycle, by author, based on Kolb’s (1984) Experiential Learning Cycle, Prentice Hall.